Information Note 1

The popular narrative of the causes of the financial crisis in the US blames a combination of relaxed prudential regulation, gaps in regulatory oversight and skewed incentives all along the originate-to-distribute chain of mortgage finance. The popularity of this narrative probably has a lot to do with the desire to identify specific culprits for the crisis, with harmful roles played by volume-focused mortgage brokers, myopic investment bankers, pliant rating agencies, captured regulators and unsophisticated investors.

An alternative view posits that innovative but flawed new mortgage structures and the opacity along the securitisation chain that had come to characterise US housing finance by the mid-2000s were enough to trigger and then propagate the crisis regardless of other contributing factors. But even within this explanation, interactions with well-intentioned but poorly designed home ownership policies, particularly those that pushed the Federal Housing Enterprises to purchase or guarantee subprime loans, likely exacerbated problems.

There are lessons for Australia in this overseas experience: well-intentioned policies to promote home ownership can increase systemic risk where they lead to higher household indebtedness and vulnerability; and regulators must understand and monitor the systemic implications of innovations in financial practices and products, particularly where they involve thin equity buffers and significant step-ups in loan repayment schedules. The recent measures announced by APRA and ASIC to re-inforce sound residential mortgage lending practices and promote responsible lending are good examples of responsible action.

US home ownership and the subprime crisis

Less well known narratives on the causes of the financial crisis emphasise mortgage innovation and home ownership policies

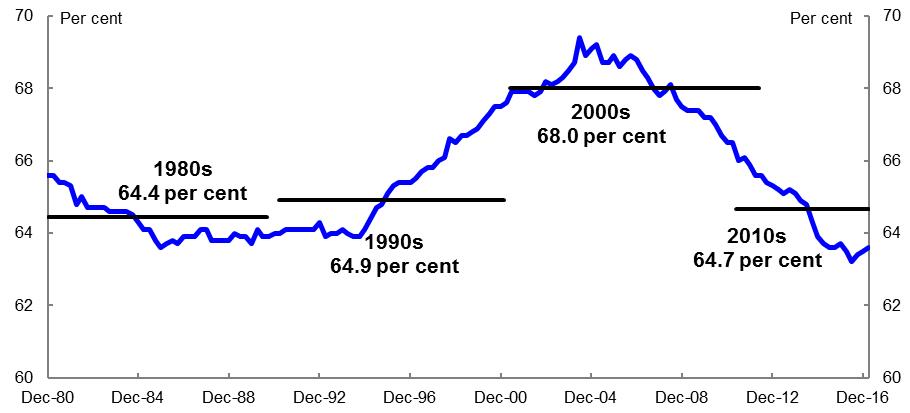

One way to look at the subprime crisis is to observe the changes in US home ownership over the last four decades. Home ownership rates in the United States rose from around 65 per cent in the 1980s and 1990s to peak around 69 per cent in the mid-2000s before declining back towards 65 per cent in recent years (Chart 1).

While movement between 65 and 69 per cent may not appear dramatic, this increase entailed more than 10 million people who had previously been unable to secure housing finance being drawn into the housing market. Increased home ownership entails many benefits to society, but it can be a concern if it is achieved through a marked deterioration in lending standards.

The role of poor lending standards as a major contributing factor to the financial crisis is well known. Other equally important narratives are less well known, possibly because they involve the unintended consequences of otherwise well-meaning policies or they do not identify specific culprits; they cannot as easily be attributed to moral failings. Among the many factors contributing to the housing boom and bust in the US, seemingly well-intentioned home ownership policies that created demand for subprime securitisations and the spread of innovative but flawed mortgage structures were key drivers2.

As more people were pulled into the housing market, prices rose rapidly creating the signal for the large increase in dwelling construction during the late 1990s and the early-to-mid 2000s, which would eventually lead to an overhang of unsold homes and the subsequent housing market collapse. With borrowers unable to sustain their housing debt, foreclosures became endemic and the home ownership rate fell to 30 year lows.

Chart 1

United States home ownership rate

Source: United States Census Bureau: Housing Vacancies and Homeownership

The role of home ownership policies

The US Federal Housing Enterprises played a key role as a source of demand for subprime securitisations

Home ownership promotes attachment to community and the work force, can improve health outcomes and can give people greater stability in retirement. Similar to Australia, the US has had a strong culture of home ownership, particularly since the Second World War, and policy makers have often helped promote its expansion through legislation such as the National Housing Act 1934 and the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act 1944 (the GI Bill).

But some of the US housing policies targeting increased rates of home ownership in recent decades, many themselves a response to the savings and loans crisis of the early-to-mid 1990s, also played a part in the US housing market collapse that triggered the financial crisis3. Starting with the administration of George H. W. Bush, but continuing under Bill Clinton and then George W. Bush, home ownership was promoted though legislation applying to the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the US Federal Housing Enterprises.

Under the Housing and Community Development Act 1992 and the Federal Housing Enterprises Financial Safety and Soundness Act 1992, HUD annually set affordable housing goals, which required the Federal Housing Enterprises—Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—to purchase an amount of low-income securitisations or otherwise support this end of the housing market4.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac couldn’t purchase subprime (borrowers with impaired credit histories) or Alt-A (low documentation borrowers) loans directly from banks as they did with conforming mortgages because by definition they did not conform to the standards set by the agencies themselves. Instead, HUD allowed them to purchase securitisations backed by these loans to discharge their responsibilities to support home ownership for low income households. Through time various administrations increased the affordable housing goals relative to the number of dwelling units they financed for regular conforming borrowers from an initial 30 per cent of conforming loan finance in 1992 to 55 per cent by 2007.

As the US housing market boomed in the early-to-mid 2000s, the affordable housing goal requirements, and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s attempts to preserve market share in the face of growing competition from the private securitisation industry, pushed the agencies to purchase or guarantee increasing volumes of residential mortgage backed securities (RMBS) underpinned by subprime and Alt-A loans. In the early and mid-2000s, the Federal Housing Enterprises purchased or guaranteed roughly a third of all newly issued private subprime and Alt-A RMBS ($434 billion alone between 2004 and 2006) and held around 15 per cent of the market’s outstanding stock5.

Though primarily an anti-discrimination policy, some also point to the Community Reinvestment Act 1977 as another source of the subprime crisis. It basically required banks that accepted deposits in low income communities to also make loans in those areas, pushing them to make more loans to those on low-moderate incomes than they otherwise would have done6.

In this way US housing policies themselves created an enormous source of demand for the problematic subprime securitisations at the heart of the US housing boom and bust. Legislators should be aware that housing policies that aim to increase home ownership should be considered carefully to avoid simply increasing the indebtedness and vulnerability of low income households..

Mortgage innovations

Option adjustable rate mortgage structures pulled previously constrained borrowers into the housing market

Flawed mortgage innovations and skewed incentives in the originate-to-distribute model were also significant factors during the financial crisis.

Households with relatively low income or ability to demonstrate a capacity to repay were drawn into the housing market by mortgage structures dependent on ever rising prices to create home equity. These included option adjustable rate mortgages (option ARMs) and negative amortisation loans in which repayments are insufficient to prevent the principal growing through time.

In particular, option ARMs, which are thought to be the structure behind between 60 and 80 per cent of subprime loans, were initially seen as a way to overcome obstacles to borrowers with poor credit histories; traditionally the interest rate needed to compensate the lender for default risks was too high for these borrowers to service the loan.

Rather than being locked into a 30-year mortgage with these borrowers, the option ARM allowed the lender to reassess after 2-3 years over which period the borrower faced a low ‘teaser’ rate that they could afford.

If after 2-3 years the borrower had made all mortgage payments on time, they were deemed to have established an appropriate credit history. If dwelling prices had risen, they also effectively now had enough equity in the home to constitute a deposit. And if both these conditions were satisfied, the subprime borrower could then effectively be treated as a prime borrower and the lender had the ‘option’ to refinance them into a regular prime mortgage.

Of course the flaw in this model was that it required rising prices to create home equity equivalent to a deposit. When further homebuyers could not be enticed into the market, even with the skewed incentives in the originate-to-distribute model and the weak lending standards it promoted—such as No Income, No Job or Assets (NINJA) loans—the market reversed, the flaws in subprime lending structures were exposed and loan servicing requirements were pushed beyond borrower capabilities.

Rather than being refinanced into prime mortgages at the option of the lender at the 2‑3 year point, the option ARM structures gave the lender the option to allow the mortgage interest rate to step up to a fairly high floating rate, often as high as 11 or 12 per cent, pushing many borrowers into default.

Lenders individually pushing borrowers into default may have been a rational (if callous) decision. But system-wide, this triggered a spiral of foreclosures and forced sales that pushed prices lower, eroding equity creation, with more borrowers pushed into default and yet more foreclosures. Even where many lenders may have been willing to engage in forbearance with subprime borrowers, the dispersed ownership of these loans through securitisation made it almost impossible to coordinate agreement for this kind of relief.

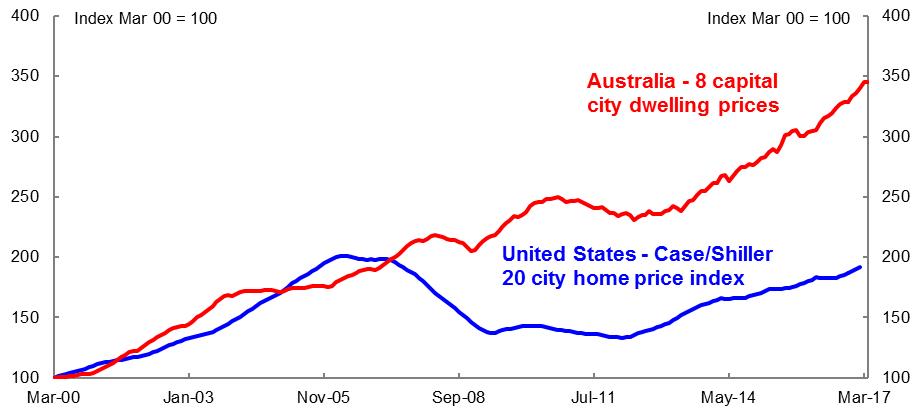

It has taken a long time for the US housing market to recover. The subprime crisis caused US house prices to fall by around a third between 2006 and 2009, and then stall for a period of several years (Chart 2)7.Since 2012, there has been a sustained recovery in house prices (rising over 40 per cent) alongside a steady reduction in the number of existing homes for sale, although in aggregate prices are yet to reach their pre-crisis levels. Measures of activity on the supply side of the US housing market, such as building permits and housing starts data, have steadily recovered since the crisis but still remain just below long-run average levels.

Australian implications

Australia has much better lending standards but continued caution with respect to interest-only mortgage lending is warranted

Australia had a comparable run up in dwelling prices prior to the financial crisis, but with better lending standards and full recourse loans, prices did not fall significantly (Chart 2). In fact, home ownership rates in Australia have fallen a little in recent decades. Other factors, including a China-driven terms of trade boom, contributed to our comparatively better economic performance.

In the period since the financial crisis, Australian regulators have tightened macroprudential policy settings in numerous ways in part to lean against the cycle but also to build the resilience of financial institutions and mortgage borrowers.

Since December 2014, The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has increased its supervisory intensity (increased reporting obligations and on-site visits) and may require banks to hold extra capital if they fail to:

- Limit investor lending growth to 10 per cent annually;

- Impose a minimum serviceability buffer of 2 per cent above the standard variable interest rate on new loans or a floor rate of 7 per cent (whichever is higher) to ensure borrowers can maintain payments in circumstances where interest rates are higher; and

- Cease high risk lending practices, such as writing excessive numbers of interest-only loans and loans over very long terms (greater than 30 years) as well as writing too many loans at high loan-to-income and loan-to-value ratios.

Between 2015 and 2017, ASIC conducted reviews into interest-only lending and mortgage broker remuneration practices, making various recommendations, including around serviceability calculations on interest-only loans and on volume-based broker commissions and soft dollar incentives8.

It remains necessary for regulators to consider the systemic implications of innovations in financial practices and products, particularly those with discontinuous repayment schedules. In this regard, the systemic risk properties of interest-only loans in Australia warrant careful monitoring and the recent measures announced by APRA and ASIC have assisted in reducing these vulnerabilities9.

Chart 2

Comparison of US and Australian house prices

Source: Bloomberg; CoreLogic

Source: Bloomberg; CoreLogic

1 The views expressed in this note are those of The Treasury and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government. This note was prepared by John Swieringa in Macroeconomic Group.

2 See Gorton, G 2008, ‘The panic of 2007’, National Bureau of Economic Research, Paper No. 14358.

3 See, for example, Greenspan, A 2010, ‘The Crisis’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, pp. 201-246 and Fama, E and Litterman, R 2012, ‘An experienced view on markets and investing’, Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 26, Issue 8, pp. 15-19.

4 Respectively established in 1938 and 1968 to increase mortgage lending at the lower end of the mortgage market, the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA) is commonly called Fannie Mae, while the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC) is commonly called Freddie Mac.

5 Leonnig, CD 2008, ‘How HUD mortgage policy fed the crisis,’ Washington Post, 10 June 2008. Note: the stock of their holdings was low relative to the proportion of new subprime loans purchased because many had structures that meant the borrower typically refinanced after two or three years increasing the prepayment speed on subprime RMBS relative to regular prime mortgages (see mortgage innovation section).

6 There is some literature discounting the role of housing policies as the source of the growth in subprime lending, particularly by authors from within the Federal Reserve System. For example, Avery and Brevoort (2011) of the Federal Reserve Board in Washington and Hernandez-Murillo, Ghent and Owyang (2012) from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis find that there are insufficient linkages between loans (or eligible securities) identified as being made under these housing policies and subsequent defaults. However, both studies rely on a methodology of looking for discontinuities around discrete housing policy thresholds that provide indirect evidence at best.

7 S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller 20-City Composite Home Price Index (NSA), sourced from Bloomberg 13 June 2017.

8 See ASIC 2015, ‘Review of interest-only home loans,’ REP445; ASIC 2016, ‘Review of interest-only home loans: Mortgage brokers’ inquiries into consumers’ requirements and objectives,’ REP493; and ASIC 2017, ‘Review of mortgage broker remuneration,’ REP516.

9 See APRA 2017, ‘Further measures to reinforce sound residential mortgage lending practices,’ letter to all Authorised Deposit-Taking Institutions, 31 March 2017 and ASIC 2017, ‘ASIC announces further measures to promote responsible lending in the home loan sector,’ Media Release 17‑095MR, 3 April 2017.